![]()

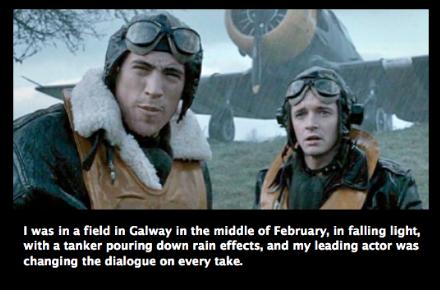

I was in a field in Galway in the middle of February, in falling light, with a tanker pouring down rain effects, and my leading actor was changing the dialogue on every take. Andrew Keagan, who had been brought in from California to play an American WWII fighter pilot, said that he wanted to keep it open, fresh, alive. Previously I had wrangled time to go through the script line-by-line with the principal cast and make any changes and adjustments that might be necessary. I had told the producers that this would save valuable time when it came to the shoot. Andrew, however, considered these not to be definitive but just possible alternatives to be tried out when the time came. Some of his other alternatives he had shared with the rest of the cast, some he had not. Now he was changing the lines so often that it was not just the other members of the cast who were getting confused; he was confusing himself.

I was reminded of my early days at Granada when, in the bar of Manchester’s Film Exchange, I met an American girl who intrigued me. She had a zany, off-the-wall, manner reminiscent of Diane Keaton’s portrayal of Annie Hall in the film of that name. I soon discovered that she was a visiting actress who had done a lot of work off- Broadway in New York and was very much a party to the “underground” theatre scene. Now she had scored a part in a play that was being produced at the studios. On the day of the recording I decided to drop by and watch from the control box. She was playing a young American, not so different from her real life self. and all seemed to going fine until, in the middle of her dialogue, she turned, walked across the set, and yanked open the door of a refrigerator. The interior was unlit and empty but for a few cardboard boxes. Suddenly there were shouts of CUT, and groans of exasperation. Immediately, the prop boys jumped up to protest to the floor manager — “We didn’t know she was going to do that. That wasn’t rehearsed.” The floor manager quietened them down before turning to ask the actress, “Why did you do that?” Mouth agape, eyes wide, she spread her hands in affronted innocence — “I was just trying to bring some life to this pile of shit!”

Coming out of the Beat movement of the 50s and the introduction of zen to the West there seemed to arise in America a mad desire to throw the preconceived to the winds and find spontaneity in the moment. At that time The Method approach to acting, taught by Lee Strasberg at The Actors’ Studio of New York held sway in that world. Among its alumni were Marlon Brando, James Dean, Paul Newman, Al Pacino and a galaxy of others. But now a number of Strasberg’s closest associates, notably Stella Adler and Sandford Meisner, broke away to develop their own system. Central to Strasberg’s Method was thepractice of connecting to a character by drawing on personal emotions and memories, known as affective memory. Meisner believed this approach made actors focus too much on themselves and their past. He described acting as

"...living truthfully under imaginary circumstances”, and encouraged actors to free themselves to react spontaneously by fully immersing themselves "in the moment”.(25)

Another who had similar differences with Strasberg was the actor and director, John Cassavetes. As a student, I had sat mesmerised through Cassavetes’ breakthrough first film, Shadows, which ended with a caption reading —

THE FILM YOU HAVE JUST SEEN WAS AN IMPROVISATION.

We now know that this was only partially true, but it was a key factor that rapidly lead improvisation to became the buzz word of the moment. The light-weight equipment that made this approach to film possible, had been developed during the war, but it was not until the late fifties, after refinements made by, Robert Drew, Richard Leacock and other pioneers of Direct Cinema that the new aesthetic possibilities were realised. Their breakthrough documentaries, such asPrimary, were a revelation because, while they were centred around crisis situations which would have been the stuff of drama, the raw way that they were presented made all current acting look contrived and old-fashioned. It was that same confrontational, unvarnished, human reality, but under imaginary circumstances, that Cassavetes set out to recreate in the movies.

Whilst producing a collage of brilliant fragments, the first version of Shadows, did not amount to a satisfactory whole. For the second shoot, which produced over a quarter of the final running time of 81 minutes, Cassavetes resorted to a fully written script.(6) This revised version achieved world-wide success, including three BAFTA nominations, and so, for his follow up film, Faces, he started out with a  draft script of 250 pages. However, during the course of the shoot, Cassavetes began accepting the “offers” made by his cast, modifying the movie as he went along, in order toncorporatei Clearly, this was not a viable way to go on making movies, but it enabled Cassavetes to discover how to script movies as if they were improvised. And, despite the fact that all his films from then on were pre-written, the idea of his films being improvised stuck. The surface effects of improvisation have been summed up, repetition, interruption, and hesitation, but Cassavetes took it far beyond that. Firstly, he removed all

draft script of 250 pages. However, during the course of the shoot, Cassavetes began accepting the “offers” made by his cast, modifying the movie as he went along, in order toncorporatei Clearly, this was not a viable way to go on making movies, but it enabled Cassavetes to discover how to script movies as if they were improvised. And, despite the fact that all his films from then on were pre-written, the idea of his films being improvised stuck. The surface effects of improvisation have been summed up, repetition, interruption, and hesitation, but Cassavetes took it far beyond that. Firstly, he removed all setting up of scenes, (even though he had resorted to this in some of the written portions of Shadows), and then he removed all other forms of, what I have called, telling, but that he called editorialising. He then assembled his scenes, not in logical progression, moving from one dramatic idea to the next, but rather from emotional impulse to impulse that shifted, with sudden changes of tone and pace — through, what I call, the feeling context — rather than pursuing any clear and simple line of motivation.

setting up of scenes, (even though he had resorted to this in some of the written portions of Shadows), and then he removed all other forms of, what I have called, telling, but that he called editorialising. He then assembled his scenes, not in logical progression, moving from one dramatic idea to the next, but rather from emotional impulse to impulse that shifted, with sudden changes of tone and pace — through, what I call, the feeling context — rather than pursuing any clear and simple line of motivation.

One of my first forays into the BBC was to direct Alan Plater’s Trinity Tales at Pebble Mill Studios in Birmingham. Under David Rose’s stewardship, this outpost had become a hotbed of innovation, with drama  commissions that would never have been approved by the London hierarchy.My show was certainly bright and original, with songs, jokes, plays within plays, pastiche and a quite raucous style of narration. But, I soon discovered that there was a parallel, but quite different form of experimental drama in production at the studios. One day I was sat in the canteen reading scripts when I became aware of a dispute going on at the next table between a props department representative and some production staff. Apparently the director had demanded that a

commissions that would never have been approved by the London hierarchy.My show was certainly bright and original, with songs, jokes, plays within plays, pastiche and a quite raucous style of narration. But, I soon discovered that there was a parallel, but quite different form of experimental drama in production at the studios. One day I was sat in the canteen reading scripts when I became aware of a dispute going on at the next table between a props department representative and some production staff. Apparently the director had demanded that a  store cupboard be filled with very conceivable piece of household cleaning equipment. For a moment I wondered whether the kookie actress from Off-Broadway had resurfaced, but then I realised that this cornucopia of practical props was demanded, not just for recording, but for the whole of rehearsals. According to the union rules this meant that props operatives would have to be standing by for the whole of rehearsal period which seemed to be extended well beyond the norm. And, what is more, it was not clear whether any of this equipment would ever be used because there was no proper script — they were just improvising.

store cupboard be filled with very conceivable piece of household cleaning equipment. For a moment I wondered whether the kookie actress from Off-Broadway had resurfaced, but then I realised that this cornucopia of practical props was demanded, not just for recording, but for the whole of rehearsals. According to the union rules this meant that props operatives would have to be standing by for the whole of rehearsal period which seemed to be extended well beyond the norm. And, what is more, it was not clear whether any of this equipment would ever be used because there was no proper script — they were just improvising.

The director causing the stir was Mike Leigh, who had come from the theatre workshop movement and, via an independent film, was now attempting to extend this way of working into the tightly scheduled, union-controlled world of TV. To actually shoot in a free-wheeling manner would, at that time, have been out of the question, but Mike’s use of improvisation was restricted to devising the drama during the rehearsal period. The actors were encouraged to base their characters on a real person that they knew, which resulted in a range of characters not often seen on screen. It also lead to a deep identification between actor and role. However, in my opinion, the process of then transcribing these explorations into a fixed script, inevitably lead to a theatricalisation of the end product.

Mike Leigh’s biggest early success, Abigail’s Party, was, in fact, derived from a theatre production and relied heavily on Alison Steadman’s wicked mimicry of a garrulous social climber. By extending his work into television and film he was able, on occasion, to focus on less articulate characters, as he had in his breakthrough film, Bleak Moments, but rules for composing the drama, which he laid down, limited narrative surprises, and restricted the final form the work could take. The most successful of his later works, Secrets and Lies, relies on the essentially

Mike Leigh’s biggest early success, Abigail’s Party, was, in fact, derived from a theatre production and relied heavily on Alison Steadman’s wicked mimicry of a garrulous social climber. By extending his work into television and film he was able, on occasion, to focus on less articulate characters, as he had in his breakthrough film, Bleak Moments, but rules for composing the drama, which he laid down, limited narrative surprises, and restricted the final form the work could take. The most successful of his later works, Secrets and Lies, relies on the essentially  theatrical ingredients of trauma, confrontation and confessional monologues. There is nothing of the febrile present moment uncertainty that Cassavetes set out to capture, or the fleeting images of time that belong exclusively to the cinema.

theatrical ingredients of trauma, confrontation and confessional monologues. There is nothing of the febrile present moment uncertainty that Cassavetes set out to capture, or the fleeting images of time that belong exclusively to the cinema.

The focus on the present moment in American acting had largely come about in reaction to what they called, The English Style of Acting, which was about the polished delivery of a text. Meisner likened the text to a canoe afloat on a raging river. The river was emotion, which was what concerned him first and foremost. “Punctuation is emotional, not grammatical,”(25) are words with which he once summed it up. I would certainly agree that the emotional pulse of the actor is more important than marks on a page, but there are things that have to be said. Emotion may be a propulsive force carrying the text forward or it may be a counter force against it being spoken, but an actor cannot give himself to embodying that emotion if he is messing with the words. By striving for spontaneity he locks himself out of the present moment and is no longer all there.

It is ironic that Sandford Meisner is best known for The Repetition Exercise in which two actors repeat to each other the same observation, over and over, until there is a felt impulse to change it. The point is not that the line is being repeated but that each time it should be said as if for the first time, in response to circumstances. Unfortunately, this has resulted in some young American actors wanting to do the very opposite and never say the same words twice. Often this can result in a mumbled mush of unnecessary grace words — all those ums and ahs and well okays — jarring substitutions and clumsy circumlocutions. It was amusing then to come across the following quote from Julie Christie :

:

“I can get distracted by the other actor doing something ... They might be coming up with their own word for something in the script, but if it doesn't make sense and it doesn't carry things through it is distracting. If they keep saying the wrong word that can subconsciously affect your attention.” (29)

Acting truthfully means getting out of your own way and allowing imaginary circumstances to become real in the same way that an hypnotic suggestion can become real for the one in a trance. This is a level of belief beyond the rational mind, beyond words