![]()

As a twenty-five year old director, still finding my feet in the world of drama, I cast the veteran actor, John Welsh, for a cameo role of a man who had seen more than he was willing to tell. I thought I had detected a reticent quality in him, perhaps not common among actors. However, in rehearsal I found that was not coming across the way that I had hoped. I suggested to him that he should play the scene without looking directly at the other actor in the scene. John looked at me wide-eyed and asked why on earth would he not look at the person to whom he was speaking. I tried to explain that a shy person is often quite fearful of looking another directly in the eye, or meeting the look of another. He shook his head as if he thought that I was quite mad, and then suggested that, as the scene took place in a conservatory, he could be preoccupied with repotting a plant.

I had given John a direction in the negative mode — not to do something. He had translated this into the positive mode by inventing the business of fiddling with plant pots. He had inserted an action in place of an avoidance. I settled for this even though I felt that it was missing the point. Many years later I saw just what I had been looking for repeated week after week on BBC television’s The Fast Show, in the Ted & Ralph sketches, brilliantly played by Paul Whitehouse and Charlie Higson. In these Ted rarely looks Ralph in the eye because he does not want to face up to the truth of

I had given John a direction in the negative mode — not to do something. He had translated this into the positive mode by inventing the business of fiddling with plant pots. He had inserted an action in place of an avoidance. I settled for this even though I felt that it was missing the point. Many years later I saw just what I had been looking for repeated week after week on BBC television’s The Fast Show, in the Ted & Ralph sketches, brilliantly played by Paul Whitehouse and Charlie Higson. In these Ted rarely looks Ralph in the eye because he does not want to face up to the truth of what he secretly knows that he would find there. This is perhaps something that could only really come across on screen and in close-up.

what he secretly knows that he would find there. This is perhaps something that could only really come across on screen and in close-up.

Musing on my failure to get this idea across to John Welsh I came to realise that the direction I had given him cut across a long theatrical tradition. One of the primary ways that the stage director can focus audience attention is by having the actor look at the person whom he is addressing and other

Musing on my failure to get this idea across to John Welsh I came to realise that the direction I had given him cut across a long theatrical tradition. One of the primary ways that the stage director can focus audience attention is by having the actor look at the person whom he is addressing and other actors on the stage to follow the conversation with their eyes until it is their turn to speak. We accept this convention without thinking but in reality the play of looks and glances is much richer and more diverse. Though acting for film and TV, supported by camerawork and editing, tends to follow the stage convention, on screen the eyes — set free — may well carry more meaning than the words.

actors on the stage to follow the conversation with their eyes until it is their turn to speak. We accept this convention without thinking but in reality the play of looks and glances is much richer and more diverse. Though acting for film and TV, supported by camerawork and editing, tends to follow the stage convention, on screen the eyes — set free — may well carry more meaning than the words.

I again stumbled on the problem of getting actors not to eyeball each other when working on the BBC series, The Prince Regent, though this time it was for quite opposite reasons. Peter Egan, who played the Prince, was an actor I did not get on well with at all well, and early in rehearsals he objected to the way I had positioned him for a long self-referential speech. I had wanted him to turn away from his auditors and step to where I could close in on him in the foreground with his listener behind.

I again stumbled on the problem of getting actors not to eyeball each other when working on the BBC series, The Prince Regent, though this time it was for quite opposite reasons. Peter Egan, who played the Prince, was an actor I did not get on well with at all well, and early in rehearsals he objected to the way I had positioned him for a long self-referential speech. I had wanted him to turn away from his auditors and step to where I could close in on him in the foreground with his listener behind.  He called this “middle-distance acting” which, he declared, he found false; so I asked him to demonstrate how he thought it should be done.

He called this “middle-distance acting” which, he declared, he found false; so I asked him to demonstrate how he thought it should be done.

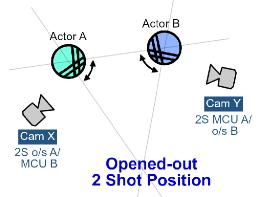

Peter took a step back and played the speech mainly looking down-right, with quick looks up to his interlocutor at the end of lines. The delivery was natural enough but what he had done without thinking was take up the stock position of the opened-out two-shot — just what I had set out to avoid. This is a position which originally came from stage convention, where two actors in dialogue, instead of facing up, would stand at ninety degrees to each other so that the audience could see their faces. Later it was adopted in film, and especially television, to allow two cameras to simultaneously shoot over-shoulder shots of the two actors without getting in each other’s picture. It was a setup which I referred to as the “cocktail party stance”, because the only people who ever stood this way in real life were guests at a cocktail party who were more interested in looking round the room than the person to whom they were speaking.

Peter took a step back and played the speech mainly looking down-right, with quick looks up to his interlocutor at the end of lines. The delivery was natural enough but what he had done without thinking was take up the stock position of the opened-out two-shot — just what I had set out to avoid. This is a position which originally came from stage convention, where two actors in dialogue, instead of facing up, would stand at ninety degrees to each other so that the audience could see their faces. Later it was adopted in film, and especially television, to allow two cameras to simultaneously shoot over-shoulder shots of the two actors without getting in each other’s picture. It was a setup which I referred to as the “cocktail party stance”, because the only people who ever stood this way in real life were guests at a cocktail party who were more interested in looking round the room than the person to whom they were speaking.

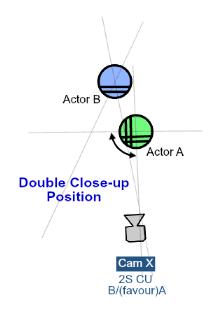

But there was also a question of inference and meaning. To look away from someone is an act of high status because it implies that you do not care one way or the other about their opinion. The way that Peter had played the scene was more akin to a fellow making an embarrassed confession to his mate in the pub. Further, by constantly glancing to his listener for confirmation he was negating the possibility of an ironic commentary on his proposals through the unhampered facial expression of his listener, which would be unseen by him, but registered throughout by the camera holding the two actors in a double close-up.

But there was also a question of inference and meaning. To look away from someone is an act of high status because it implies that you do not care one way or the other about their opinion. The way that Peter had played the scene was more akin to a fellow making an embarrassed confession to his mate in the pub. Further, by constantly glancing to his listener for confirmation he was negating the possibility of an ironic commentary on his proposals through the unhampered facial expression of his listener, which would be unseen by him, but registered throughout by the camera holding the two actors in a double close-up.

It is an interesting discovery to make that when we are not looking at the person with whom we are speaking our eyes betray more of what is going on in our mind than when we do. This is known in Neuro- linguistic Programming as the Eye-accessing Cues”. Once you have become aware of these movements they are so obvious that it is astonishing that they were not formally recognised until the nineteen seventies. Some of the more obvious cues were, of course, instinctively known to actors; such as the flirtatious look held a beat too long followed by the lowering eyes down right to access feelings. Or, the guilty sideways look right when an alibi is broken. the point is that if an actor is experiencing his role, and not just going through the motions, when he is not looking directly at the person he is addressing his eyes are by no means dead, but just the opposite

.

In a masterclass for BBC Television, that was much-talked about by actors, and was later published as a book, Michael Caine said:

“Blinking makes your character seem weak. Try it yourself: say the same line twice, first blinking and then not blinking. I practiced not blinking to excess when I first made this discovery, went around not blinking all the time and probably disconcerted a lot of people. But by not blinking you will appear strong on screen. Remember: on film that eye can be eight feet across.”(5)

However, as I think Michael began to realise, this unblinking stare is the look of the psychopath.

In everyday conversation our direct looks are very, very, brief. Anything longer has immediate implications. I discovered this for myself when editing a conversation between Anthony Forest and Cecile Paoli for Bergerac. In the scene Anthony Forest’s character harbours an ulterior motive which he disguises behind flirtatious banter; while Cecile’s character is charmed by him but uncertain as to what his intentions really are. A key segment had been shot in separate closeups and I soon discovered that altering the length of an exchange of looks by just one frame (1/24 of a second) on either side of the cut could completely change the implication of the scene, from a brush-off to a promise, from naive acceptance to deep suspicion.

has immediate implications. I discovered this for myself when editing a conversation between Anthony Forest and Cecile Paoli for Bergerac. In the scene Anthony Forest’s character harbours an ulterior motive which he disguises behind flirtatious banter; while Cecile’s character is charmed by him but uncertain as to what his intentions really are. A key segment had been shot in separate closeups and I soon discovered that altering the length of an exchange of looks by just one frame (1/24 of a second) on either side of the cut could completely change the implication of the scene, from a brush-off to a promise, from naive acceptance to deep suspicion.

Later on in his masterclass Michael Caine takes a different tack and talks about rationing your looks:

“One of the finest practitioners of this technique is Marion Brando. He denies the camera his eyes. Half the time he's looking down or away. Then suddenly he looks up, and you are absolutely fascinated by his eyes. (5)

I would like to suggest that it was not so much that Brando was hiding his eyes but that the camera had been set up on the assumption that he would be looking at the person to whom he was speaking, but, in fact, for much of his performance he was engaged in internal processing. It was this that gave his performances such lingering fascination.