![]()

I have always found actors fun to be with. When they are good they are delightful company; open, bright, witty, generous ... But when they are bad ... An old adage among directors is that if you say you’ve never had problems with actors, you’re lying. Bad behaviour by actors, it would seem, goes with the territory. For the director it is an occupational hazard: you can bend over backwards to try to avoid it , but, sooner or later, it will unexpectedly rise up out of nowhere and leave you floored.

Actors can sometimes be breathtakingly pompous. They can also be astonishingly ungrateful. One minute they are pigging out on your food and drink, the next they are thinking twice about sharing their car with you or as good as ignoring you in the lift. They have a tendency to edit their lives the way they edit their credit lists whenever they fancy they might be getting a tad closer to their starry ambitions. I have come to the conclusion that all actors, whether they are on the dole or have their name in lights, secretly think they are still owed the acclaim that is their due. For most the constant rub of the mundane reality of their everyday lives against the glorious sturm und drang of their emotional lives keeps them permanently in a state of irritation, that is always bubbling just below the surface. In the movie Whithnail & I, a film about a jobbing actor without a job, this existential divide takes on such epic proportions that the title character, played by Richard E. Grant, soon  became a real-life T-shirt hero — though, judging from audience numbers on the movie’s first release, I suspect, this following was pretty much confined to the insiders and wannabes of the profession.

became a real-life T-shirt hero — though, judging from audience numbers on the movie’s first release, I suspect, this following was pretty much confined to the insiders and wannabes of the profession.

One small-part actor, whom I met socially, reminded me of the irrepressible Whithnail. He was a friend of a friend and so, despite his manic brio, I knew that, in truth, he was having a tough time surviving in the business. From then on whenever I had a small part for which the casting was not too critical I would put it his way..Until, after one such occasion, when he arrived on set and I went over to greet him, he stopped me in my tracks, drew me aside and whispered, “If I do this part for you this time I shall expect a better part next — a lot better.” It was apparent that in his mind it was him doing the favours and not me. To sack him on the spot, which I felt like doing, would have been out of proportion, but I made sure that I never employed him again. Obviously my help with paying his grocery bills meant less to him than his over- blown narcissistic pride.

In Whithnail & I there is just such a situation that chimes with this experience: Whithnail, who appears to be terminally unemployed, quips that he thinks his agent must be dead, and then goes on:

“Something's got to be done. We can't go on like this. I'm a trained actor reduced to the status of a bum. I mean look at us! Nothing that reasonable members of society demand as their rights! No fridges, no televisions, no phones. Much more of this and I'm going to apply for meals on wheels.”

And then, out of the blue, he gets a call from a director with work on offer but his reaction is, surprisingly, less than jubilant:

“Bastard asked me to understudy Constantine in The Seagull. I'm not going to understudy anyone, especially that little pimp. Anyway, I loath those Russian plays. Always full of women starring out of windows whining about ducks going to Moscow.”

Among the crew actors are sometimes referred to as, "the dummies", "the retards", "the aliens”, but, most often, simply as "the children" — I've even heard actors, without rancour, refer to themselves that way. John Badham, whose credits include Saturday Night Fever, advising young directors on how to work with actors, goes so far as to suggest they should study a book by Dr. Thomas Gordon, called P.E.T. — parent effectiveness training.(2) However, the most forthright and vicious attack on the behaviour of actors has come from, writer and director, David Mamet. After describing film people as “the salt of the earth”, he goes on to liken actors to a bunch of self- indulgent plutocrats who terrorise with their tantrums or fool around playing “heartless silly japes to lighten the mood”.(21)

Among the crew actors are sometimes referred to as, "the dummies", "the retards", "the aliens”, but, most often, simply as "the children" — I've even heard actors, without rancour, refer to themselves that way. John Badham, whose credits include Saturday Night Fever, advising young directors on how to work with actors, goes so far as to suggest they should study a book by Dr. Thomas Gordon, called P.E.T. — parent effectiveness training.(2) However, the most forthright and vicious attack on the behaviour of actors has come from, writer and director, David Mamet. After describing film people as “the salt of the earth”, he goes on to liken actors to a bunch of self- indulgent plutocrats who terrorise with their tantrums or fool around playing “heartless silly japes to lighten the mood”.(21)

For very many actors, I think there is a reversal of the usual mindset associated with going to work and that of going on holiday. Arriving on set, frequently on location, with a clearly defined character and role ahead is, for the actor, an escape from the diffused anxiety of everyday living. There will be a new build-up of tension as the moment approaches when they must step forth and deliver their performance; but, on their first arriving one senses among the actors a feeling of release. Sally Potter has suggested that, while most of us live in retreat from our own skin, actors must be full of themselves on set in order to be fully alive before the camera. Certainly, one can appreciate that a certain degree of brio is necessary to breakthrough the shyness barrier; but if these spirits once raised are not harnessed to the job in hand they can soon spill over and become malignant.

JI have often overheard actors in huddles swapping stories of their colleagues outrageous behaviour in which they all seemed collectively to take an evil delight. However, it only gradually dawned on me that this was an attitude that could often be deliberately cultivated. I once worked with a young actor on the verge of stardom who spent much of his free time thumbing through lurid accounts of Hollywood high jinx. One day we were shooting a difficult hand-held tracking shot through streets and alleyways. Every time he messed up by not hitting marks or missing cues he would pull funny faces, make hooting noises, or otherwise play to the crowds. The shot was being executed by a veteran cameraman, who himself was something of a prima donna; after a number of repeats, he suddenly stopped, thrust his camera towards an assistant and retorted in a stentorian voice, “When you decide to behave like a professional call me.” And with that he stomped off. The actor suddenly looked like a little boy who had been rapped over the knuckles. With tears welling in his eyes he mumbled, as if in justification, “I thought I was meant to be the star around here.”

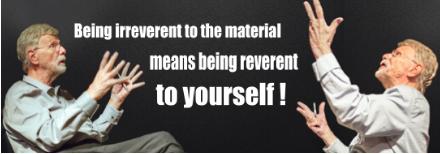

Since that time I have discovered that in Los Angeles there is a school of acting that goes beyond the well-worn practices of Method Acting to what it’s controversial guru, Eric Morris, calls Irreverent Acting. This approach might be summed up with the catchphrase — “irreverence to the material encourages reverence to the self.“ This comes down to the basic tenet that the actor must open himself to the moment-to-moment subconscious flow of experience and express his real feelings regardless of context and

Presence/Performance 98

Eric Morris

regardless of circumstance.

“Accepting irreverence is accepting yourself, it is acknowledging that who you are, how you express yourself, and the way you experience the world are the most important things you have to contribute to the planet. It means having the courage not to run scared under the pressure of the take or an entrance onto the stage. It means standing your ground and allowing, permitting, accepting, and including all that you feel, and encouraging the expression of that.”(26)

He goes on to proudly relate how he encouraged an actress to honour her impulse and let out a blood-curdling scream in the middle of a scene much to the bewilderment of writers and directors in the audience. To me this all harks back to the long discredited 60s — “let it all hang out” — ideal of free expression. It flies in the face of the fact that any real character that is half-way to being a normal human-being comes complete with limitations and inhibitions. Indeed, in popular parlance this is just the qualities that make up “character”, which results from having weathered the “slings and arrows of fortune.” In real life it is only at moments of trauma and psychological disorientation that raw experience, so beloved by The Method school, breaks through.

It is not the director’s job to act as therapist or guru or acting coach — actors emotional blocks need to be dealt with but that is for them and them alone. Acting is not acting out and the portrayal of character is not simply a vehicle for the actor’s own self-expression. Liv Ullman has pertinently drawn this distinction.

"There are two ways of crying: one is that you allow your character to cry; but the other is that you get so moved by yourself that you cry. And then you are in deep trouble, because then you are into self- involvement. That's a danger for a lot of actors — their work becomes too much feeling — they cry their own tears and that isn't art.”(4)

Morris, who refers to himself as “a professional experiencer”, seems to conflate drama with psychodrama. Nowhere does the word self-indulgence enter into Morris’s system, or, indeed, humility. One exercise included in Irreverent Acting is called Feeling Special:

“If the actor gets in touch with being special and unique, he will be much more willing to take chances expressing his impulses. Since accepting irreverence as an approach to acting starts with the intellect, convincing ~ yourself that there isn't any alternative is a good starting place. As an inner monologue or out loud, express all the things that you feel are special, unique, and exciting about yourself.”(26)

Surely this comes instinctively to all actors? It is just this that prompts them to first step forward into the spotlight. And it is just this that needs to be checked and tempered by artistry.