![]()

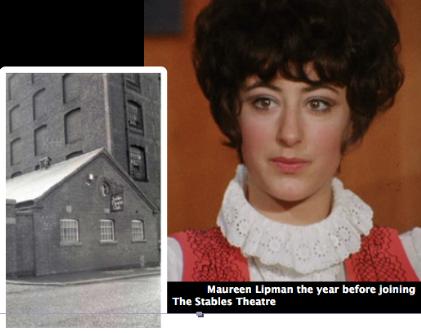

No-one taught me how to go about working with actors. It was taken for granted that this was something any would-be director had to work out for himself. The first chance I got was at The Stables Theatre Club in Manchester, where I directed short plays with such future luminaries as Richard Wilson and Maureen Lipman. However, an ongoing part of the schedule, in which I was also expected to participate, was, devoted to “workshopping”. This was very much a trend of the time that followed on from the leads of New York’s Living Theatre, Peter Brook’s resuscitation of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, and Jerzy Grotowski’s Poor Theatre. At The Stables these sessions, that focussed on group work, physical expression and improvisation, were frequently lead by, my friend and neighbour, John Downie, whose mantra was, “process before product.” I could see how this might be liberating for an actor, but I could not agree that this was an appropriate motto for a director to have on his T-shirt. It struck me that this was, in fact, shrugging off the director’s prime responsibility, which was specifically to the end- product.

No-one taught me how to go about working with actors. It was taken for granted that this was something any would-be director had to work out for himself. The first chance I got was at The Stables Theatre Club in Manchester, where I directed short plays with such future luminaries as Richard Wilson and Maureen Lipman. However, an ongoing part of the schedule, in which I was also expected to participate, was, devoted to “workshopping”. This was very much a trend of the time that followed on from the leads of New York’s Living Theatre, Peter Brook’s resuscitation of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, and Jerzy Grotowski’s Poor Theatre. At The Stables these sessions, that focussed on group work, physical expression and improvisation, were frequently lead by, my friend and neighbour, John Downie, whose mantra was, “process before product.” I could see how this might be liberating for an actor, but I could not agree that this was an appropriate motto for a director to have on his T-shirt. It struck me that this was, in fact, shrugging off the director’s prime responsibility, which was specifically to the end- product.

When I began training at Granada TV the first director whom I shadowed was Derek Bennett. He too had become caught up in this trend, and often began rehearsals with some kind of theatrical game.I soon learned, however, that the more seasoned actors, and particularly those who were orientated towards working on screen rather than the theatre, found all this an embarrassing waste of time. This was a relief because I felt much the same. This group work was not what screen acting was about; It was the internalised, often solitary moments that counted for most on screen.Once while, I was watching from the the multi-camera control room, production was halted while some technical problem was solved, but the actors remained in position,with cameras lined up on them, closeups on the monitors before me. As they sat doing nothing, thinking about — who knows what? — I was struck by how very intimate this experience was. Rarely in real life do we watch anyone with such close scrutiny except, perhaps, our closest loved-ones, and then only for moments.

![]()

On the surface it would appear that actors are the most open and egalitarian of groups, where people of all ages, classes and backgrounds mix freely with each other. In practice, one soon findsthat on any set a very definite pecking order is soon established. The stars like to tell the supporting actors what to do, the supporting actors like to tell the bit players what to do, and the bit players like to tell the extras what to do. There is then another hierarchy of age, accolades, and longevity on the production. On Fallen Hero there was a two-episode intensely emotional storyline that focused on the wayward son of the female lead, Dorothy, (played by Wanda Ventham). Cast in this role was a quirky but sensitive young actor, called John Wheatley, and it was evident that this was the most demanding thing he had yet done. He very evidently needed my input but I soon noticed that some of the older members of the cast were getting fidgety with the amount of time I was spending with him.

On the surface it would appear that actors are the most open and egalitarian of groups, where people of all ages, classes and backgrounds mix freely with each other. In practice, one soon findsthat on any set a very definite pecking order is soon established. The stars like to tell the supporting actors what to do, the supporting actors like to tell the bit players what to do, and the bit players like to tell the extras what to do. There is then another hierarchy of age, accolades, and longevity on the production. On Fallen Hero there was a two-episode intensely emotional storyline that focused on the wayward son of the female lead, Dorothy, (played by Wanda Ventham). Cast in this role was a quirky but sensitive young actor, called John Wheatley, and it was evident that this was the most demanding thing he had yet done. He very evidently needed my input but I soon noticed that some of the older members of the cast were getting fidgety with the amount of time I was spending with him.

![]()

So, I decided to work with Johnseparately from the rest of the cast, one-on-one. This was made easier because the story climaxed in an unusually long monologue which ended in an emotional breakdown. When we came to the shoot John was quite mesmerising. Immediately that I shouted CUT he collapsed into a sobbing heap on the ground, and Del Henney (who played the lead, Gareth) turned and walked off the set. It took several minutes to bring John round; I then went to find out what was wrong with Del. He shook his head — nothing was wrong — he just could hardly bear to watch such raw emotion.

Always under pressure of time in the run-up stages of a shoot I several times brushed off, or made light of, actors requests to meet for a chat. I have since come to realise that the one-on-one is an essential step in the process. This was strikingly brought home to me by an actor at the other end of the scale in experience. This was Ian Bannen, who had been nominated for an Academy Award and twice for a BAFTA. On Bookie Ian would just mark through the scenes then wait until he saw that I had a moment spare, take me aside, and, often gripping my forearm and holding his face only inches from mine, run through his lines for the scene, just leaving gaps when others spoke. He would play these at reduced volume, but, otherwise, giving clear indication of the performance he would give for the take. In effect, he was offering up a big close-up of the scene while at the same time putting me in the position of a close-up from which he could read the nuances of my immediate reactions.

![]()

In European cinema there has always been an accepted focus on fulfilling the director’s vision. Because our practice in Britain has largely been derived from the theatre and the text, it has taken a long while for this one-on-one communication between actor and director to become accepted as a necessary stage in the process.

In European cinema there has always been an accepted focus on fulfilling the director’s vision. Because our practice in Britain has largely been derived from the theatre and the text, it has taken a long while for this one-on-one communication between actor and director to become accepted as a necessary stage in the process.

Recently Jude Law commented on the evolution of his own practice.

“... what's happened more and more in my process is that I've sought that experience of working with the director one-on-one before we've been in a more communal environment. In fact my whole process has changed quite considerably ... I can feel solid in a role, when I've had that one-on-one experience and asked all those questions and looked at everything. I demand it now. Not by 'being demanding' but just to say, 'I really need this time with you to ask you this, this and this.' (29)

The screen image is one of extreme intimacy; it rarely evokes or relies on the same collective experience as the theatre.

Presence/Performance 8