![]()

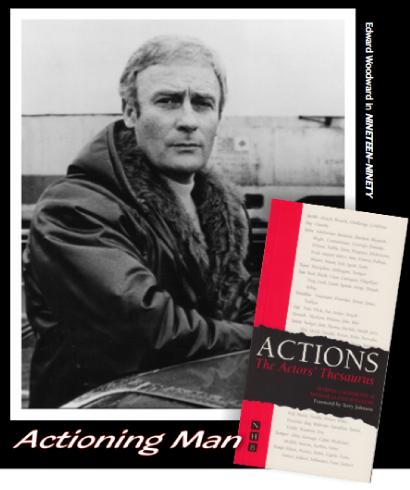

My first shoot for BBC London was a series set in the near future, called Nineteen-Ninety, starring Sir Edward Woodward. Teddy, as he was known to friends and colleagues, could be a charming man, and on occasion went out of his way to be kind to me, but he was not the easiest actor to work with. Blocking one of the early scenes I asked him to turn away at a certain point and move to the desk. He stood stock still and asked, “Why?” I suggested that he did not want people to see his face while he was thinking things through. He considered this for a moment and then said, “Yes, but why move to the desk?” I thought hard and fast and then suggested that he had left there on his scribble pad some bullet points that would guide hisnext move. He stared at me blankly, knowing that I had just made this up on the spur of the moment; then, he nodded, okay — he would give it a try. The impasse was broken and we went on with the scene.

I had quickly grasped that Teddy was not going to make any move unless he had a logical reason for doing so; but this is not at all the way we behave in real life — we stare out of the window, tidy objects, move from one chair to another, tap out a rhythm, stop when we catch sight of ourselves in the mirror, walk just for the pleasure of moving and so on. Dancers begin by learning a set of moves and then gradually discovering in their own bodies the feelings that these express, the spirit that flows through them. Sometimes this same approach is needed in film: think of Jeanne Moreau’s solitary walk through the town in La Notte, or the near-speechless pas de deux of Alain Delon and Monica Vitti through the old apartment as a prelude to making love in L’Eclisse. Antonionni was notorious for giving only external direction; these actors were able to use it to create wonderful moments of screen presence. However, when he worked with actors from an English theatre background, Richard Harris (Il Desserto Rosso), Vanessa Redgrave (Blowup), the results were less successful, resulting in them often looking stiff and self- conscious on screen. Counter to this, David Hemmings, whose background was in classical music, gave a career defining performance in the latter film because he recognised that movement was more important than the words spoken

.

.

V![]()

In the English theatre the tradition is that the text comes first, and the actor’s job is seen as bringing the text alive. To escape the curse of recitation and rhetoric, in recent times the practice has grown up of actioning. One of the champions of this approach was the director, Max Stafford Clark, who would begin rehearsals of a new play with several weeks of just breaking the text down into “action units”. Theidea behind this stems from the famous Russian theoretician, Stanislavski, who decreed that an actor must always have an objective in a scene. The action is what the character does to achieve that objective — though it is more likely to reside in words and gestures rather than the kind of action implied by action movie.

In the theatre this may well be a technique that can bring immediacy to a scene by going beyond mere words to foreground the on-stage interaction between characters. But this approach results in an externalisation of performance and a focus on purpose and logic which often misses what is at the heart of screen drama.

For example, in my play The Personal Touch, about two middle-aged singletons meeting through the personal column of a newspaper, the actioning was all quite stereotypical; the appeal of the piece was in the unintended exposure of vulnerabilities of the two main characters, played by Stuart McGugan and Morag Hood.

For example, in my play The Personal Touch, about two middle-aged singletons meeting through the personal column of a newspaper, the actioning was all quite stereotypical; the appeal of the piece was in the unintended exposure of vulnerabilities of the two main characters, played by Stuart McGugan and Morag Hood.

In the early days, multi-camera television drama was developed by pre-marking cuts on a dialogue script. All but the most obvious  reactions off-dialogue were difficult to anticipate with precision and had to rely on off-the-cuff adjustments made by the vision mixer. The best coped with this brilliantly but it was inevitably a hit-and-miss affair. With reactions timing is crucial; just two frames difference in how long a look is held, for example, can completely change the meaning of the interaction. Further, only the most assured performances could bear the scrutiny of being shot in this way. The shortcomings of a performance would often be shown up, the actor’s mind wandering between speeches to mentally rehearse (or just remember) the next line they were due to say.

reactions off-dialogue were difficult to anticipate with precision and had to rely on off-the-cuff adjustments made by the vision mixer. The best coped with this brilliantly but it was inevitably a hit-and-miss affair. With reactions timing is crucial; just two frames difference in how long a look is held, for example, can completely change the meaning of the interaction. Further, only the most assured performances could bear the scrutiny of being shot in this way. The shortcomings of a performance would often be shown up, the actor’s mind wandering between speeches to mentally rehearse (or just remember) the next line they were due to say.

With modern digital film techniques the use of the reaction shot has become very much easier. However, inexperienced actors still make the assumption that they will be on camera when they are speaking — at least for their most telling lines; but not when the position is reversed. Few actors understand that the cut-point for reaction shots will frequently be made when their consciousness goes from outside to inside, or vice-versa — when they are registering

With modern digital film techniques the use of the reaction shot has become very much easier. However, inexperienced actors still make the assumption that they will be on camera when they are speaking — at least for their most telling lines; but not when the position is reversed. Few actors understand that the cut-point for reaction shots will frequently be made when their consciousness goes from outside to inside, or vice-versa — when they are registering