![]()

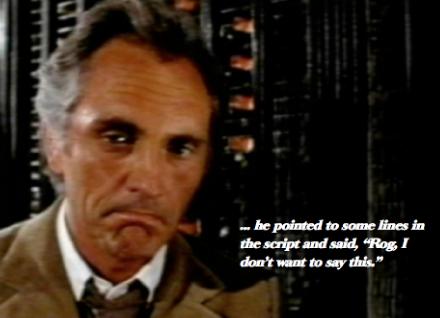

Before we started work on Deadly Recruits Terence Stamp told me that, as far as he was concerned, the director made the film and his job as actor was to offer up the material from which I, as director, could construct my vision. However, in practice, I soon discovered that there were definite boundaries to the things that he thought would be right for him to do, or to wear, or to say, and, on occasion, these could come as a surprise. One day he called me over on set, pointed to some lines in the script and said, “Rog, I don’t want to say this.” Normally, I would have been sympathetic, but I knew that these lines had been added at the request of the producer to cover a gaping hole in the plot. I explained this to Terry. He was silent for a minute and then said, “Get someone-else to say them will you?”, and walked away. From this I learnt that you do not ask a star to carry exposition.

Actors sometimes get carried away by the romantic notion that they are part of the great tradition of storytellers who would recite their tales in the flickering light of the camp fire; but on screen an actor’s job is not to tell stories,but to embody characters and any mixing of the two ends up in confusion. The actor’s performance is, of course, borne along on the narrative flow but any attempt at indicating what is to be understood implies an audience and opens up a division between character and situation. Timothy Spall refers to actors as “depicters” (29), but whether pictorial or verbal any knowing address to an audience is a burden that detracts from the actor’s immediate presence on screen.

A few years later, while shooting Winners & Losers, there was an incident that hit closer to home because the objection was to lines  that I had written. Theselines were not simple exposition: the objection was that they contained the title of the piece,though not out of context in the present scene. Leslie Grantham and Denise Stephenson were in agreement that the line “clanged”. I did not know what they meant; I thought the line was pretty smart and the scene would be poorer without it. I told them I would like it to be kept in and walked away. But, after a few paces, I suddenly got what they meant. Any repeat of the title would obtrude as an ironic comment to which the characters in the scene were not party. I went back and told them to cut it.

that I had written. Theselines were not simple exposition: the objection was that they contained the title of the piece,though not out of context in the present scene. Leslie Grantham and Denise Stephenson were in agreement that the line “clanged”. I did not know what they meant; I thought the line was pretty smart and the scene would be poorer without it. I told them I would like it to be kept in and walked away. But, after a few paces, I suddenly got what they meant. Any repeat of the title would obtrude as an ironic comment to which the characters in the scene were not party. I went back and told them to cut it.

It is not the actor’s job but the director’s job to tell the story. But, neither is it the actor’s job to directly express the director’s ideas. The actor must start from his visceral response to the scene, not from imposed ideas. Recently, Sam Mendes has put forward his 25 Rules for Directors, #7 of which reads:

“If you are doing a play or a film, you have to have a secret way in if you are directing it. Sometimes it’s big things. American Beauty, for me, was about my adolescence. Road to Perdition was about my childhood. Skyfall was about middle-age and mortality. Sometimes it’s small things. Maybe it’s just a simple idea. What if we do the whole thing in the nightclub, for example. But it’s not enough just to admire a script, you have to have a way in that is yours, and yours alone.” (22)

Certainly, I can agree with this; the director’s vision is the centre pole on which everything else depends — sometimes a big idea, sometimes little ideas. But, with regard to actors what I would emphasise is that little word “secret”. Just as the actors should be allowed their secret keys to the character they will inhabit, so the director needs to keep the ideas for his movie to himself. The directors idea is really only a perspective from which the actor’s work is seen; the two cannot be collapsed into the same space.

There is one more excuse for telling (or, in actors’ parlance, indicating) that has crept in since the rise of the script gurus in the eighties. Some actors now ask questions about “character arcs” and “turning points”. Does an actor really need to know this? Or is it just another ploy to side- step the heavy lifting of embodying a living, breathing, human being?

Acting coach, Howard Guskin, has an interesting take on this: he believes that storytelling, including character, is the province of the writer and director, and not the actor.

“... it is best not to think about the story. Just go with the flow. Otherwise your effort to make sense of the story will show, and your acting will become repetitive, predictable, and melodramatic. Even when you know exactly where the story is going, you must never play the story. .” (14)

I feel this is too extreme: in film-making, where the actor has to cope with scenes being shot completely out of order, he must have a grasp of where his work fits into the whole, just has he must retain an awareness of his movement relative to the set and the shot. But, certainly, I would agree that the actors primary responsibility is to the truth of the moment and not the meaning.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()