![]()

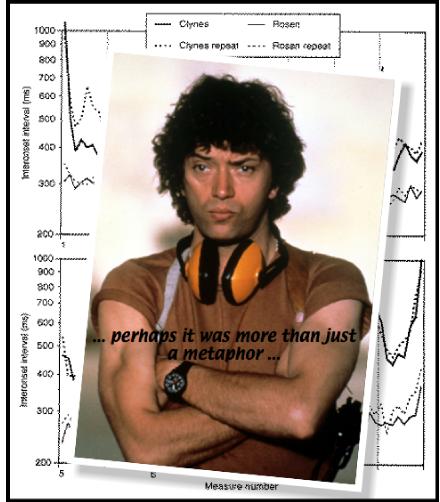

I first met Martin Shaw a year, or perhaps longer, before we worked together. He was proselytising for est (Erhard Seminar Training) that had just hit London. The claim was that in two weekends it would transform your life. Martin, along with a bunch of other actors had been among the first to sign up, and said that it was the only thing that had kept him sane while doing The Professionals.

The story was that Martin had signed a contract which would keep him exclusive to the show for five years. These long contracts were new to Britain at that time, and, further, the ethos here had always been that if an artiste really did not want to do something they would be released or a compromise reached. However, the independent, Mark One

Productions, who were aiming to introduce the American model of production to Britain, had other ideas. When, after the first hit series, Martin asked to be released they refused and threatened to block any future employment and sue him for every penny he had.

The problem for Martin was not just the gruelling schedules but the total lack of development in the role that he played. He had been formally trained at LAMDA, appeared opposite Olivier at The National, and been cast as Banquo in Polanski’s MacBeth. Now he being was asked to endlessly repeat a character that, to all intents and purposes, was a cypher. This was not by omission, but by deliberate design. Any reference to the background of his character, Doyle, or to his private life was ruled out. One never even saw

was ruled out. One never even saw

![]()

![]()

![]()

where he lived.In one episode of the final series he was allowed to have a girlfriend, but this was begun and ended within the one episode. It was common practice in these sort of series that any character arc was kept to a minimum for the simple reason that the producers wanted to be able to rearrange the order of episodes for optimum impact on transmission. In The Professionals this was made an absolute rule. Whereas, in Shoestring, for example, reference was often made to Eddie’s past as a drunk who had suffered a nervous breakdown, nothing was allowed to be known of Doyle or his cohort in the series, Bodie (played by Lewis Collins).

In a curious way est paralleled this. It was said that the training offered people the opportunity to free themselves from a life enmeshed by their past, and to experience themselves whole and complete in the present moment. In a cannily planned sequence of interactions It brought together many of the preoccupations that had brewed up in the sixties — the “no mind” of zen, the mental processes of Scientology, and Fritz Perl’s Gestalt Therapy, with it’s mantra — “Get out of your mind and come to yoursenses.” The training was set out to empower participants not to be choked by the “meaning” of their past but simply to be alive in the moment — creating something from nothing. Or, in the succinct words of it’s founder, Werner Erhard, it took you from what’s so to so what?.

A moment-to-moment narrative without a past was a challenge not just to actors, but to directors, like myself, who were bent on going beyond the basic storytelling requirements and set conventions of shooting. I groped my way towards the thread that still held everything together — action, dialogue, camera, technical and scenic requirements — the thread that I called, the inner score. Actors are rarely much interested in larger rhythms and contrasts over the whole work but they are interested in finding pattern and shape within their own scenes. The inner score was a way of finding something to grasp onto beyond words on the page, a perspective from which to see one moment as different from the previous and the following — moments of slowness and speed, changes of focus, and the flow from external to internal and back again. Even in action sequences, to gain depth and resonance, there must be moments of internalisation — moments of emotion, reaction and decision. If the heat of the moment is too great for pause then these will be deferred, but , in time, there must come a return to that natural rhythm.

Around this time I came across a book that took the idea of the inner score to a whole new level It was written by the bona fide genius, Manfred Clynes; a man who was, not only a world-class concert pianist, but distinguished neuroscientist, and computer whiz who invented the word “cyborg”; amongst his friends were both Albert Einstein and Pablo Casals. His thesis was that beneath our experience of touch, gesture, emotion, music and art there were certain universal brain wave patterns, which he labelled essentic forms. He experimentally demonstrated that these were constant through differing forms of expression across all cultures. In one trial, for example, Aborigines in Central Australia were able to correctly identify the specific emotional qualities of sounds derived from the touch of white urban Americans. Even animals who share a similar consciousness of time exhibit these same dynamic forms, hence the intuition of pet owners that their dog or cat understands tone of voice and the emotions expressed by touch.(8)

Around this time I came across a book that took the idea of the inner score to a whole new level It was written by the bona fide genius, Manfred Clynes; a man who was, not only a world-class concert pianist, but distinguished neuroscientist, and computer whiz who invented the word “cyborg”; amongst his friends were both Albert Einstein and Pablo Casals. His thesis was that beneath our experience of touch, gesture, emotion, music and art there were certain universal brain wave patterns, which he labelled essentic forms. He experimentally demonstrated that these were constant through differing forms of expression across all cultures. In one trial, for example, Aborigines in Central Australia were able to correctly identify the specific emotional qualities of sounds derived from the touch of white urban Americans. Even animals who share a similar consciousness of time exhibit these same dynamic forms, hence the intuition of pet owners that their dog or cat understands tone of voice and the emotions expressed by touch.(8)

So, perhaps the idea of the inner score goes beyond just being a metaphor. Here is Charles Marowitz talking to Glenda Jackson:

C.M. “So the director has to be an instigator of energies, and those energies are the ones that are, in a sense, trapped under the scene, and it is the collaboration between the actor and the director that releases them?”

G.J. “Yes.” (23)